Global Sub Dive supplied a research vessel, two manned submersibles, and a team of technical divers in collaboration with NOAA Office of National Marine Sanctuaries to visit the remains of three World War II ships that were involved in battle off the coast of North Carolina. The wrecks of the Bluefields and U-576 lie a mere 600 feet apart on the sea floor more than 35 miles off the coast of North Carolina, just outside of Monitor National Marine Sanctuary.

This mission is divided into two segments: The first focuses on U-576 and the Bluefields, located at roughly 700 to 800 ft deep. The second half focuses on other targets that are shallower but have not been seen.

The Battle of the Atlantic was the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, running from 1939 to the defeat of Germany in 1945, and was a major part of the Naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allied naval blockade of Germany, announced the day after the declaration of war, and Germany’s subsequent counter-blockade. It was at its height from mid-1940 through to the end of 1943.

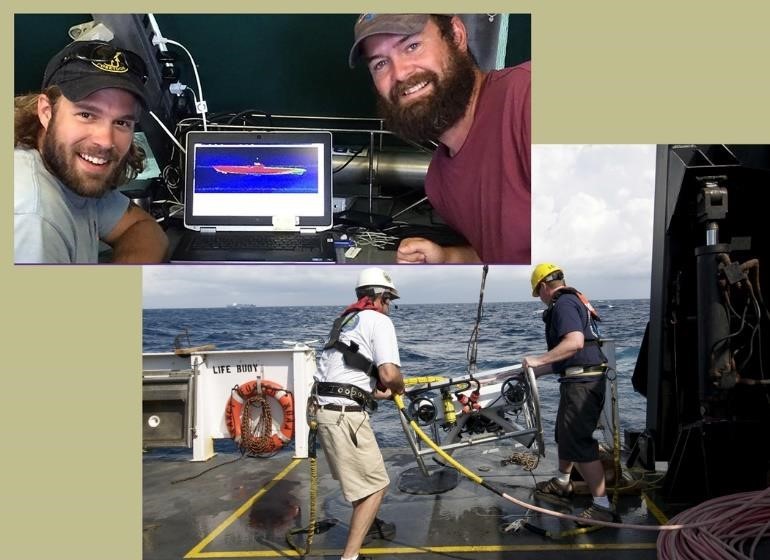

Global Sub Dive’s Triton 1000/2 submersibles served as the primary means of collecting data from the U-576 and Bluefields while BGL/Project Baseline/GUE divers used photogrammetry to 3D model the YP-389, over 300 feet deep.

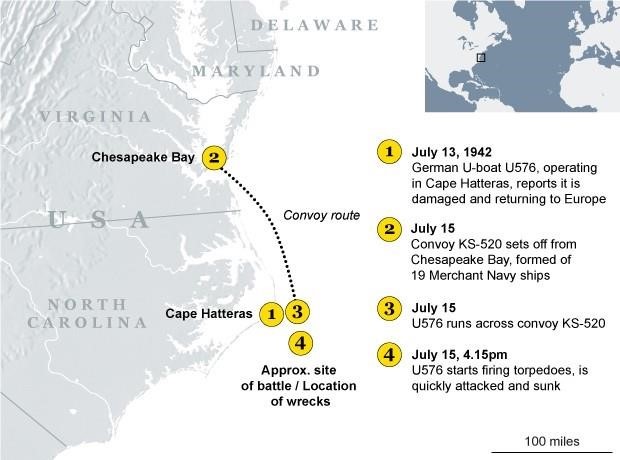

In 1942, as WWII was escalating in both scale and cost, one of the most important but understated components of the war – the Battle of the Atlantic – was waging on, outcome uncertain to either side, and alarmingly close to the American coast. This battle, unlike most that have become so familiar and well-studied, pitted largely unarmed merchant seamen and their vessels against the stealthy and deadly German U-Boat fleet. On 15 July 1942, convoy KS 520 was one such group of 19 merchant ships traveling from Norfolk VA to Key West FL. As it was passing Cape Hatteras NC, it was attacked by the German U-boat U576, itself damaged from a previous engagement and in route back to Germany. Seeking a final victory over the allies, Captain Hans-Dieter Heinicke gave the order to open fire on the convoy. The battle unfolded quickly. U576 quickly sank the Nicaraguan flagged freighter Bluefields and severely damaged two other ships, U.S. Navy Kingfisher aircraft while the merchant ship Unicoi attacked it with its deck gun. Within minutes, both the U576 and the Bluefields had fallen to the ocean floor, Bluefields without its crew who abandoned ship and were promptly rescued, but U576 with all its souls aboard.

Fast forward to 2014, 70 years after teh Allied victory over Germany, finds a team of scientists and archeologists led by the National Oceanic and Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, exploring the east coast of the US to find, identify, and describe shipwrecks of historical importance before they fade from our national memory. Working 30 miles off the coast of North Carolina in more than 800 feet of water using scanning devices that were not even dreamed of when the two ships sank, they encounter signals from their equipment that reveal the presence of two sunken ships, within only some 200 yards of each other, that are later revealed to be U576 and its last victim, the Bluefields. Led by Joe Hoyt, the team immediately recognizes the site as a critical discovery that will shed light on the least known chapter of American history, victory in the Battle of the Atlantic.

To meaningfully explore and document such a historically relevant find so close to American shores, the NOAA team determines to not only scan the wrecks and describe their lifeless physical dimensions, but to somehow get people down to their decks, to see and film these causalities of war in person such that their story can be revealed to the world as more than decaying objects on the ocean floor, but as the vessels of human spirit and determination that they both represent.

The problem is that, despite their depth of resources lacks the capability to readily put manned submersibles on the seafloor. To solve the problem, and in the spirit of collaboration, they determine to partner with a private team of explorers and conservationists who operate on a research ship with two 2-person submersibles and some most accomplished divers and submariners, Global Underwater Explorers.

Over the course of nearly 20 years the Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) have trained and cultivated a network of more than 10,000 highly skilled technical divers that operate in small teams on a volunteer basis to explore all manners of underwater environments (reefs, wrecks, caves, lakes, rivers, springs) around the world. Going beyond the excitement and rigors of exploring these uncharted places, more than 60 of the GUE teams have committed themselves to recording how the underwater world is changing through time – for good or bad – through a conservation effort they call Project Baseline.

After decades of mostly anonymous accomplishments, like being the first to find or reveal lost and famous ship wrecks including the Swedish warship Mars and the HMHS Britannic, or record-setting exploration and mapping of underwater caves in the Yucatan Peninsula, Florida, Turkey, China, and Serbia, one of GUE launches an unprecedented perpetual mission called Global Sub Dive that aims to re-engage human exploration of the undersea world as emissaries for Project Baseline using manned submersibles working in conjunction with GUE divers at depths down to 1000 feet below the surface from a 150-foot private research vessel called the Baseline Explorer.

Baseline Explorer is rolling gently 30 miles offshore of Cape Hatteras North Carolina. Some 350 feet below, Nemo and Nomad, carry NOAA scientists to the decks of another previously lost and as yet unidentified American ship that went down in the Battle of the Atlantic.

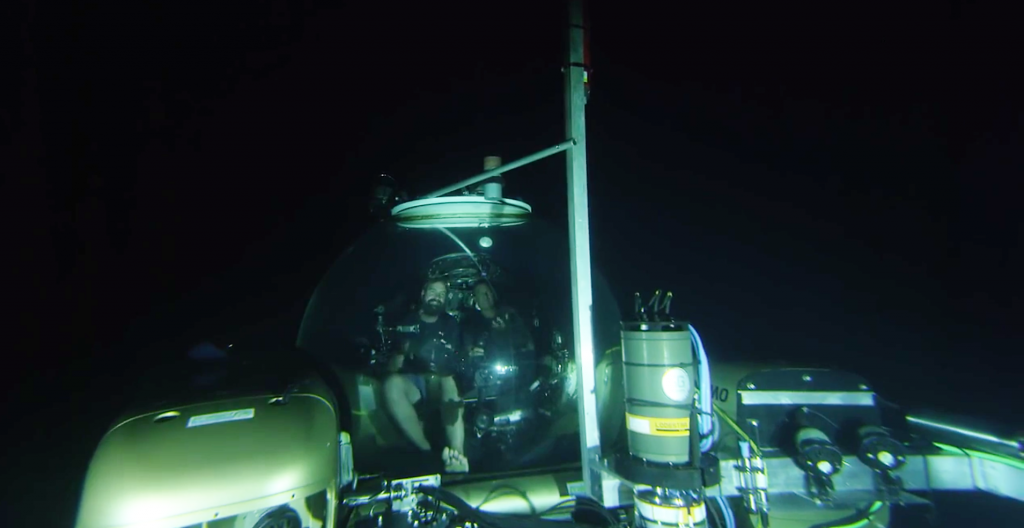

The mission on U576 was a huge success and ended just a day earlier. There, both subs descended to more than 800 feet where the only natural light is a faint eerie glow from the surface. The submariners and scientists however illuminated the wrecks of U576 and the Bluefields for the first time in more than 70 years using powerful LED lights and laser scanners mounted to the front of their tiny submersibles. The data they collected will be used to develop precisely-scaled 3D models of the vessels that will allow the rest of us normal surface dwellers to see and connect with the wrecks and this nearly lost period of history.

Today, the team is exploring one of a series of identified as other probable causalities of the Battle of the Atlantic using remote sensing equipment called side-scan sonar which is akin to echolocation used by whales and dolphins to find their way through the dark seas. 350 feet below the Baseline Explorer, the two submersibles are again hovering over the ghosts of ships that once crisscrossed the Atlantic Ocean to transport needed supplies to the beleaguered British citizens and soldiers. This time however, the submariners watch as a team of three divers buzz through the tangle of ghost fishing nets draped over the hull and superstructure riding behind diver propulsion vehicles that look like small torpedoes except with high definition cameras and lights mounted on top. One diver approaches the transparent sphere. Messages scribbled on water proof paper are exchanged between the diver and an archeologist inside the submersible across the 6-inch thick acrylic. The divers are directed to collect close-up imagery of specific sections of the ship that will help with the subsequent identification effort. They also disappear for minutes at a time into the decaying hulk of steel passageways to film key interior locations like the bridge, the engine room ocean. Working together, the scientists, submersibles, and divers accomplish in one mission what would be otherwise impossible in ten.

In total, their time together on the wreck will be a little less than an hour. The submersibles will remain longer to conduct the laser scans and allow the scientists more time to observe the outer parts of the ship. The submersible crews will be topside again in less than three hours. Once back on board the Baseline Explorer, they’ll climb out of their tiny transparent spheres and resume the day’s otherwise routine activities. The divers on the other hand must leave the wreck after only around 45 minutes after GUE diver being directed by scientist in GlobalSubDive’s submersible which they’ll begin a painfully slow ascent to the surface that will last five or more hours. At about 230 feet, where neither the wreck, the bottom, or the surface are within view, they begin stopping every ten feet for progressively longer periods, just a minute or two at first but by the time they’re within sight of the surface, each stop will be for tens of minutes or even more. At each stop they cling together around a single line that extends to a small float, bobbing in the swells above, unable to talk to each other or anyone at the surface. They will float in the open ocean for hours, drifting along feeling like bait on the end of God’s fishing line constantly peering into the vast blue emptiness, watching out for sharks, looking for anything to help pass the time, and constantly listening for the hum of the motors from the support boat that hopefully doesn’t lose sight of that float. Nearly six hours after descending, they’ll surface and slowly climb aboard the 25-foot support boat, chilled to the bone, exhausted, thirsty, and famished. With nothing but open-ocean on the horizon in any direction, the 3 divers and 3 support crew will begin their hour plus ride back to the Baseline Explorer. They’ll arrive as everyone else is finishing dinner where they’ll give their video, pictures, and any other data to the anxiously waiting but well-fed scientists.